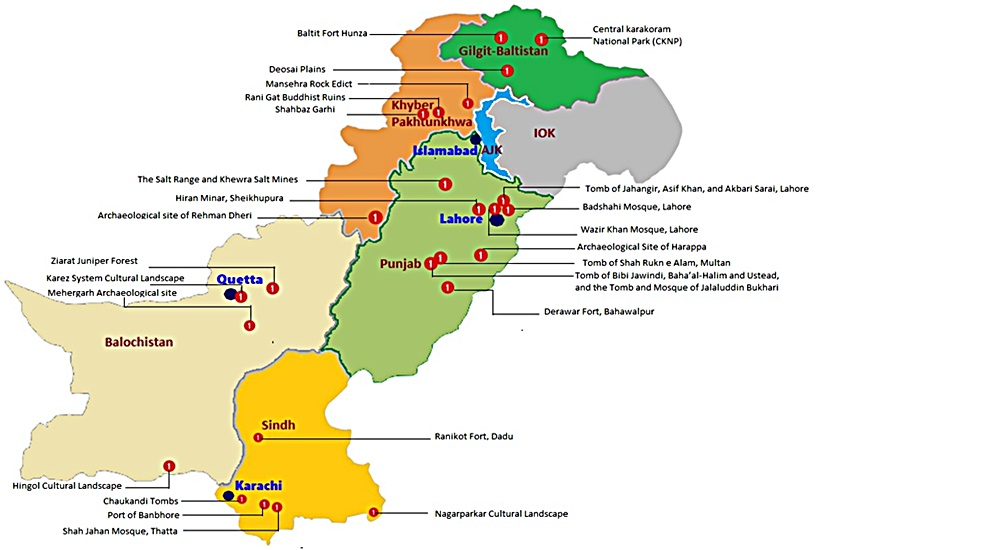

Tentative List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Pakistan

Pakistan boasts six UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In addition to these established sites, the country has compiled a roster of 25 potential sites called the Tentative List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Pakistan seeking recognition. This catalog has been formally presented to the UNESCO Committee for assessment and approval. The pre-listing process is a mandatory step for the eventual acceptance of nominations onto the esteemed World Heritage list.

Punjab Province

The Salt Range and Khewra Salt Mine

The Salt Range, rising abruptly from the Punjab plains in Pakistan, spans 180 km and features sheer escarpments, jagged peaks, and fertile valleys. Originating 800 million years ago, it formed from the evaporation of a shallow sea and underthrusting of the Indian Plate. Named for the thickest rock salt seams globally, the range is a geological treasure with fossiliferous stratified rocks and exposed strata, attracting global geologists. The region is rich in paleontological finds, including dinosaur trackways, Cretaceous belemnites, and ancient hominid remains. The Salt Range is a historical and cultural hub with sites dating from Alexander the Great‘s era to the British colonial period. Notably, Khewra hosts one of the world’s richest salt deposits, exploited for over a millennium, continuing as a mining, research, and tourism center.

Badshahi Mosque, Lahore

The Badshahi Mosque and its expansive courtyard are elevated on a platform accessible from the east via a grand staircase and a traditional Mughal-style gateway. The entrance, a two-story structure, boasts intricate decorations with framed and carved paneling on all facades. Square minarets with pseudo-pavilions in red sandstone and white marble cupolas adorn the four corners. Its tall octagonal minarets are positioned at the courtyard’s corners. Additionally, smaller octagonal minarets are attached to the prayer chamber’s corners, beneath three grand marble domes. The red sandstone exterior is subtly adorned with white marble inlay lines and patterns. The interior and exterior of the prayer chamber feature unique and beautifully crafted Zanjira interlacing and floral motifs in bold relief, showcasing unparalleled beauty and craftsmanship in Mughal architecture. The gateway’s inscription indicates its construction in A.H. 1084 (1673-74 A.D.).

Wazir Khan Mosque, Lahore

The Wazir Khan Mosque, covering an area of 279′ x 159′, is entirely constructed using cut and dressed bricks laid in kankar lime, with minimal use of red sandstone in the gate and transept. The courtyard is split into two sections, with the upper part slightly elevated and an ablution tank in the middle. Flanking the east, north, and south sides of the courtyard are 32 small hujras of varying sizes. The prayer chamber on the west side features five compartments divided by massive piers supporting wide, four-centered arches, each topped with a dome. Small rooms are created at the northern and southern ends, and an eastern gallery leads to a spiral staircase accessing the roof. Distinctive structural elements include four corner minarets, five domes, and a transept at the entrance gate on the east. According to inscriptions, the mosque was built in A.H.

Archaeological Site of Harappa

The archaeological site of Harappa, extending over 150 hectares, comprises eight mounds and two cemeteries situated to the south of the dry Ravi riverbed. While much of the site is buried beneath agricultural land or the modern village of Harappa, exposed structures on mounds AB and F date back to the third millennium BC. The site’s sequence spans from the fourth to the second millennium BC, with a depth of over 13 meters. The strategic location beside the old course of the Ravi River granted inhabitants access to trade networks, aquatic resources, and water for cultivation, explaining its prolonged occupation. Harappa’s town plan during the mature Harappan period (2600-1900 BC) features self-contained walled centers on raised mounds. The site’s unique urbanization declined in the second millennium BC, and subsequent developments, including brick removal for railway ballast in the 1850s and salination from irrigation agriculture, impacted the preservation of structures.

Tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, Lahore

The Tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan, and Akbari Sarai, designated on December 14, 1993, showcase remarkable Mughal architecture. Jahangir’s Tomb is a single-story structure with a square plan, featuring tall octagonal corner towers and a projecting entrance bay on each side. The exterior boasts red sandstone facing with intricate marble inlay decoration. The interior displays floral frescoes, delicate inlay work (pietra dura), and vibrant marble intersia. Asif Khan’s Tomb, an octagonal structure with a high bulbous dome, stands in a vast garden. Originally adorned with rich stone inlay and bold stucco tracery inside, it featured a high bulbous double dome covered with marble veneering. Akbari Sarai, between Jahangir and Asif Khan’s, includes an open courtyard with small cells, adorned gateways, and a mosque with three splendid domes. The Sarai and the entrance gateway seem part of a unified complex from Shah Jahan’s era, sharing similar styles and elements.

Hiran Minar and Tank, Sheikhupura

The Hiran Minar, erected under Emperor Jahangir’s reign in 1620 AD, boasts unique architectural elements. Its facade sports 210 square perforations arranged in 14 rows, while inside, a spiral staircase with 108 steps leads to the top, adorned with 11 rectangular arched openings. Divided into six tiers, the Minar showcases lime plaster possibly embellished with floral or linear frescoes. An arched entrance graces the lowest tier. Across from it lies a rectangular tank connected by a causeway to an octagonal baradari. Each corner features square pavilions with gateways. The tank, equipped with ramps, parapet walls, and staircases, connects to the Aik rivulet via a channel. Inside the baradari, intricately decorated niches and honeycomb patterns adorn the walls. The causeway, supported by 21 pointed arched pillars, links the main baradari to an octagonal platform in the tank’s center, which served as a royal residence.

Tomb of Hazrat Rukn-e-Alam, Multan

The tomb of Shah Rukn-i-Alam, constructed between 1320 and 1324 AD by the Tughluq ruler Ghiyas-ud-din, was initially meant for his dynasty but later dedicated to the family of the revered Sufi saint. This three-tiered octagonal structure, located at the north-western edge of the Fort, features thick walls supported by corner towers, reaching a height of 35 meters. Built with red brick and Sheesham wood, the exterior displays intricate ornamentation, including carved brick, wood, and blue and white faience mosaic tiles. Geometric, floral, and arabesque designs, along with calligraphic motifs, embellish the octagon. The interior, originally plastered, houses the sarcophagus of the saint, surrounded by those of 72 descendants. A pilgrimage site drawing over 100,000 visitors annually, the tomb reflects enduring reverence for Shah Rukn-i-Alam, with his carved wooden mehrab considered among the earliest examples of its kind.

Tomb of Bibi Jawindi, Baha’al-Halim and Ustead, and the Tomb and Mosque of Jalaluddin Bukhari

The proposed property encompasses five monuments at the southwest corner of Uch Sharif, showcasing the town’s exceptional architecture. The oldest is the 14th-century AD tomb and mosque of Central Asian Sufi Jalaluddin Bukhari. The brick-built tomb, measuring 18 meters by 24 meters, features carved wooden pillars supporting a flat roof adorned with glazed tiles in floral and geometric designs. The interior includes a partition for purdah, graves of the saint and his relatives, and a painted ceiling with floral designs in lacquer. The mosque, constructed with cut and dressed bricks, spans 20 meters by 11 meters, supported by 18 wooden pillars, and is embellished with enameled tiles. Connecting these structures are a series of domed tombs, richly decorated with carved timber, cut and molded brick, and blue and white mosaic tiles. The three domed tombs erected for various individuals exhibit intricate details despite erosion.

Derawar and the Desert Forts of Cholistan

The Cholistan desert, also known as Rohi, is a western region of the Thar Desert in modern Pakistan. Archaeological evidence reveals its past as a fertile area watered by the Hakra River, sustaining an Indus Valley culture until approximately 600 B.C. when the river altered its course. The medieval forts, including the prominent Derawar Fort, were built by local clans in the 16th to 18th centuries to protect desert caravan and pilgrimage routes. Derawar was constructed in the 9th century and later controlled by the Nawabs of Bahawalpur. It stands as a massive square structure with decorative bastions. These forts, showcasing diverse architectural forms, cluster within a 250 km N-S and 100 km E-W area, emphasizing their strategic connection to water sources and trade routes in the desert landscape. Derawar, strategically located near ancient water deposits, has served as a crucial stopover for caravans traversing the desert for centuries.

Sindh Province

Rani Kot Fort, Dadu, Sindh

The extensive fortification wall of Rani Kot spans 35 kilometers, connecting desolate hills in a structure erected during the early 19th century. This formidable wall, designed to harmonize with the natural terrain, features robust semi-circular bastions strategically placed at intervals. Encompassing three sides of the area, the fortification wall utilizes the towering peaks of higher hillocks on the northern side as a natural barrier. Approximately 5-6 miles within the main gate stands a smaller fortress, likely serving as the royal residence for the Mirs ruling family. Positioned to the south of the fortress, a double-door gate welcomes visitors. Inside the gate, two niches showcase ornate floral designs and carved stones. The entire architectural composition of the fort is characterized by the use of stone and lime.

Shah Jahan Mosque, Thatta, Sindh

The mosque, a sturdy brick structure constructed on a stone plinth with robust square pillars and massive walls, is organized around a 169′ x 97′ courtyard, mirroring the size of the prayer chamber. Large domes shelter both areas. Arcades open onto the courtyard from two aisled galleries on the north and south sides. The entire structure boasts ninety-three domes, likely contributing to a distinctive echo, allowing prayers in front of the Mibrab to resonate throughout the building. Remarkably, the mosque features the most intricate display of tile-work in the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent. The two primary chambers are entirely adorned with tiles, exhibiting meticulously arranged mosaics of radiant blue and white tiles on their domes. Elegant floral patterns, reminiscent of seventeenth-century Kashi work from Iran, embellish the spandrels of the main arches. At the same time, geometrical designs on square tiles are organized in a series of panels.

Port of Banbhore, Sindh

Banbhore is situated 65 kilometers east of Karachi on the Northern Bank of Gharo Creek. It unveils a historical span from the 1st century BC to the 13th century AD. While its early phases are waterlogged, the site preserves the best example of early Islamic urban form in South Asia and a well-preserved medieval port. The port’s impressive layout includes a 10-meter-high mound with a 3-meter-wide limestone fortification wall, featuring 46 bastions and 3 gates. The mound is divided into Western and Eastern Sectors, with structures like a mosque, administrative quarter, and serai. The stone-built mosque, dated to 727 AD, stands as the region’s best-preserved early mosque. Beyond the walls, unfortified suburbs with eroded mud brick structures extend to the East and North West. Banbhore’s strategic location at the Indus mouth, international trade connections, and eventual decline due to natural shifts underline its historical significance.

Chaukhandi Tombs, Karachi

The expansive Chaukhandi graveyard, spanning two square miles, houses the tombs of warriors from the Saloch families who settled in the area during the 17th and 18th centuries A.D. Due to the lack of dated inscriptions, precise dating of the tombs is challenging. Constructed in a pyramid form on raised platforms, these tombs feature decorative stone slabs adorned with relief carvings depicting human and figurative designs. Predominantly family graveyards, a few tombs are sheltered by pillar canopies in Hindu style. Carvings on male graves often depict a horseman with arms like a shield, sword, bow, and arrow. Female graves showcase carved ornaments such as bracelets, necklaces, rings, and anklets. Additionally, boss-shaped projections on male graves are designed to secure the deceased’s turban at the northern end.

Nagarparkar Cultural Landscape

The Cultural Landscape of Nagarparkar, situated at the southern edge of the expansive Thar desert. It features old stabilized dunes meeting tidal mudflats of the Runn of Kutch and the Arabian Sea. Historically a Jain center, the area housed the influential Jain community. It dominated trade through the port of Parinagar in the 5th century BC. Traces of the port remain visible in Dotar village. The Karunjhar hills, a pilgrimage site named Sardhara, contain Jain temples and sacred spaces linked to Lord Mahavira and Parsanatha. The wealth of the Jain community is reflected in temples at Nagarparker, Gori, Viravah, and Bodhesar, dating from the 12th to 15th centuries. The Gori temple, an exquisite example, features a main temple and 52 smaller shrines, adorned with paintings of Jain religious imagery. While Jain influence declined due to shifting seas, remnants of the Jain legacy remain in Nagarparkar’s cultural landscape.

Balochistan Province

Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh

The archaeological site of Mehrgarh, located in the Kachi plain near the Bolan Pass’s mouth, features low mounds next to the Bolan River. Covering 250 hectares, the site reveals deep accumulations of alluvium with exposed mud-brick structures, suggesting functions such as storage. The excavated remains span over 11 meters, dating from the seventh to the third millennium BC, representing a classic archaeological tell site. The chronological sequence includes Aceramic Neolithic, Ceramic Neolithic, Early Chalcolithic, and Chalcolithic periods. Mound MR3 shows the earliest Neolithic evidence, with the focus shifting to MR4 during the Neolithic-Chalcolithic period. By 2600 BC, the settlement transformed into a substantial Bronze Age village, showcasing craft specialization. Despite abandonment before the Indus Civilization’s urbanized phase, Mehrgarh offers insights into evolving subsistence patterns, craft, and trade specialization. Excavations by the French Archaeological Mission revealed well-preserved mud-brick structures in recent trenches.

Hingol Cultural Landscape

The Hingol Cultural Landscape is declared reserved in 1988. It encompasses diverse landscapes, from the Arabian Sea to beaches, estuaries, and the Dhrun Mountains. The shrine, located in a natural cave along a stream leading to the Hingol River. It lacks a temple structure but features a low mud altar. Hinglaj Mata Mandir, situated in Hingol National Park along the Makran coast, about 190 km west of Karachi, is a revered Hindu religious site linked to the Charani tradition of goddess worship. As a Shakti Peetha, it is believed to be where the head of goddess Sati fell during her dismemberment by Vishnu. Hindus visit throughout the year, with a religious gathering called “Hinglaj Mata Teerath Yatra” drawing over 5,000 pilgrims in April. Additionally, pilgrims visit mud volcanoes in the park, notably Chandragup and Khandewari, associated with the convergence of tectonic plates in the Makran coastal area.

Ziarat Juniper Forest

The Ziarat area in Pakistan boasts the world’s second-largest juniper forest, covering about 110,000 ha. The Ziarat Juniper Forest is home to ancient junipers. It is considered among the oldest living trees globally, with some estimated to be thousands of years old. This forest is in the mountain zone with an elevation ranging from 1,181 to 3,488 masl. It harbors high species diversity and sits at the junction of five vegetation zones, making it globally distinctive. Hosting endangered wildlife such as the Balochistan Black bear and Sulaiman Markhor, along with diverse plant species, the forest is a vital biosphere reserve declared in 2013. Recognized for its significance in climate change studies, the Ziarat Juniper Forest serves as a crucial carbon stock, playing a pivotal role in carbon sequestration efforts. Despite being under pressure, its designation as a biosphere reserve emphasizes protection and sustainable development.

Karez System Cultural Landscape

The Karez system in the Balochistan desert stands as a remarkable model of ancient water management in arid environments. Originating in Persia in the 1st millennium BC, the technology spread along the Silk Route, reaching Balochistan and Xinjiang, China. Karez consists of vertical shafts and sloping tunnels tapping into subterranean water, efficiently delivering it to the surface by gravity. These systems, crucial for inhabitation, create culturally rich landscapes closely tied to the communities they serve. Managed by shareholders who buy 24-hour cycles, or “shabanas,” Karez systems connect water access to social structures and community identity. Despite facing threats, there are approximately 1,053 functioning karezes in Balochistan, irrigating 27,000 hectares. Four representative Karezes are proposed for inclusion on the Tentative List are:

- Spin Tangi Kareze, District Quetta

- Chashma Achozai Kareze, District Quetta

- Ulasi Kareze, District Pishin

- Kandeel Kareze, Muslim Bagh, District Killa Saifullah

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province

Archaeological Site of Rehman Dheri

The archaeological site of Rehman Dheri in Dera Ismail Khan, KPK province, encompasses a rectangular mound of approximately 22 hectares, rising 4.5 meters above the surrounding landscape. Visible structures from the final phase reveal a well-planned settlement with a grid of streets and lanes dividing the area into regular blocks. The surface exhibits eroding kilns, slag, and scattered artifacts, providing a glimpse into small-scale industrial areas. With a depth of over 4.5 meters, the archaeological sequence spans over 1,400 years from around 3,300 BC. The site represents three distinct periods: I (c. 3300-3850 BC), II (c. 2850-2500 BC), and III (c. 2500-1900 BC). Rehman Dheri, abandoned during the mature Indus phase by the middle of the third millennium BC. It offers an exceptionally preserved example of early urbanization in South Asia.

Archaeological Site of Ranighat

Ranighat is a renowned Buddhist archaeological site in Tehsil Totalai, District Buner, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It boasts scattered remains along the ridge in the valley. Explored by notable researchers like Sir A. Cunningham and H.W. Bellew in the 19th century, it faced illegal digging and destruction by treasure hunters in 1898. Protected under the Antiquities Act of 1975, Ranighat is currently undergoing preservation efforts. The excavated area is divided into four sectors, all protected with barbed wire fencing. Various facilities and development works, including an approach road, stepped path, wire fencing replacement, shelters, entrance gate, and site cleanup, have been implemented to ensure proper conservation and presentation of the historic site.

Shahbazgarhi Rock Edicts

The Shahbazgarhi rock edicts are inscribed on two large boulders within a rocky outcrop in the Vale of Peshawar. They provide a record of fourteen edicts from the Mauryan emperor Asoka (c. 272-235 BC). These edicts, dating back to the middle of the third century BC, offer the earliest incontrovertible evidence of writing in South Asia. Scripted in the Kharosthi script, the edicts are written from right to left. The presence of Kharosti indicates the enduring influence of Achaemenid rule in the Gandhara region, surpassing the brief Alexandrian period in the fourth century BC. Positioned alongside an ancient trade route connecting the Vale of Peshawar with Swat, Dir, and Chitral to the North, as well as Taxila to the Southeast, these edicts shed light on various aspects of Asoka’s dharma or righteous law.

Mansehra Rock Edicts

The Mansehra rock edicts are inscribed on three large boulders along a rocky outcrop near the city of Mansehra, documenting fourteen edicts of the Mauryan emperor Asoka (c. 272-235 BC) and standing as the earliest incontrovertible evidence of writing in South Asia. Dating back to the mid-third century BC, these edicts are scripted from right to left in the Kharosthi script. The presence of Kharosthi suggests the enduring influence of Achaemenid rule in the Gandhara province, surpassing the brief Alexandrian interlude of the fourth century BC. These fourteen major edicts, found alongside an ancient route connecting the Vale of Peshawar to Kashmir, Gilgit, and Central Asia in the north and the significant city of Taxila in the south. It offer insights into various aspects of Asoka’s dharma or righteous law.

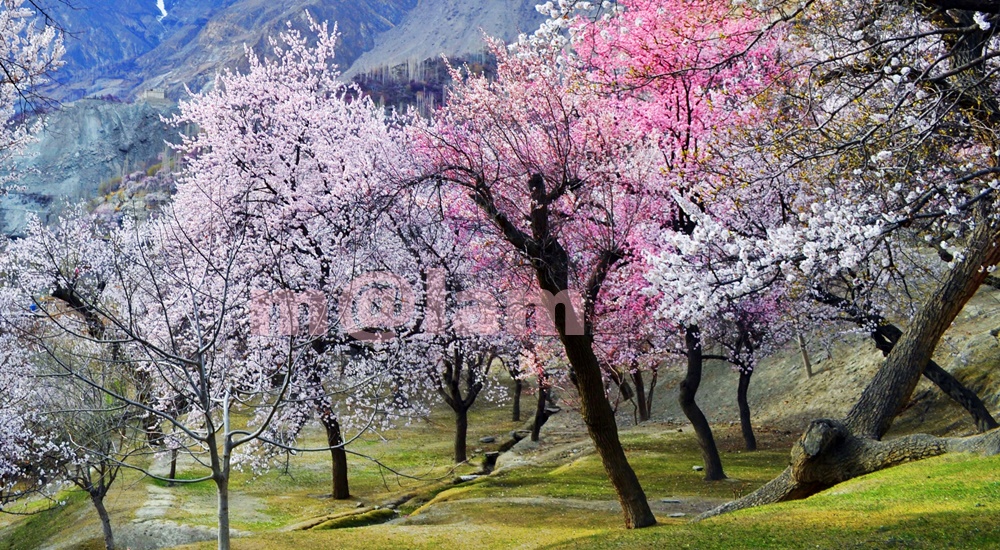

Gilgit-Baltistan

Baltit Fort, Hunza

The magnificent Baltit Fort is located in Karimabad, the former capital of Hunza. The fort is strategically positioned with a commanding view of the Hunza Valley. The rectangular fort, rising from an artificially flattened spur below the Ulter Glacier. It has played a crucial role in controlling the seasonal trans-Karakoram trade between South and Central Asia. With three floors, it features storage chambers on the ground floor, an open hall on the first floor, and winter living quarters on the second floor. The third floor, partly open, includes a summer dining room and reception hall. Inhabited by the Mir, ruler of Hunza until 1945, the fort underwent conservation in 1990. It reveals an eighth-century core tower augmented over time. The stone walls, strengthened by an internal timber framework, highlight architectural stability in an area prone to seismic activity.

Central Karakorum National Park (CKNP)

Declared a national park in 1993, CKNP is the world’s largest protected area. It encompasses over 10,557.73 km2 in the Central Karakorum mountain range. This high-mountain system, formed 20 to 60 million years ago due to tectonic activity. It experiences intense geomorphological events like landslides, creating new landforms amid destruction. Covering 40% of the area by glaciers such as Hispar, Biafo, Baltoro, and Chogo Lungma, the park is crucial for its fragile ecosystem. The transitional zone between arid Central Asia and the semi-humid tropics of South Asia, CKNP hosts diverse ecosystems. These include alpine pastures and conifer forests, providing a refuge for threatened species like snow leopards, musk deer, and Marco Polo sheep. The park’s significance extends to its avifauna. Approximately 90 bird species part of one of the largest migratory bird routes globally.

Deosai National Park

Deosai National Park, an alpine plateau in the western Himalayas, covers 358,400 ha. at 3500 to 5200 m. Characterized by undulating plains surrounded by mountains, it contrasts sharply with the narrow valleys and steep mountains nearby. Enduring extreme cold and aridity, Deosai receives higher snowfall than neighboring valleys. Positioned at the convergence of two biogeographical provinces, the park serves as a watershed for three significant river systems. Featuring high-altitude wetlands, including Sheosar Lake, the park supports unique alpine ecosystems with meadows, willows, and wildflowers. Designated in 1993, the park is vital for conserving the critically endangered Himalayan Brown Bear. It is part of Conservation International’s Himalayan Biodiversity Hotspot. It’s also an Endemic Bird Area, showcasing diverse flora and hosting 72 bears, marking it as the only stable population in the western Himalayas.